Tomoko Sato, Exh. cat, Czech Republic.: Mucha Foundation Publishing, 2015. Essays by Paul Green & Claire Allerton, Alison Brown, Sandra Penketh, and Jo Meacock, 168 pp., 118 colour ills., 42 b/w. £20.

Exhibition schedule: Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum, Bournemouth, April 1, 2015 – September 27, 2015; Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norfolk, November 7, 2015 – March 20, 2016; Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum, Glasgow October 8, 2016 – February 19, 2017; Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, June 16, 2017 – October 29, 2018.

Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Nov 07, 2015 – Mar 20, 2016

In Quest of Beauty is an exhibition which is designed to not only promote the work of Alphonse Mucha, but to study the theoretical idea of ‘beauty’ that was a core principle of Mucha’s art. In Quest of Beauty is an exhibition specifically looking at Mucha’s Paris period and his art work after he returned to his native Czechoslovakia. Critical reviewers largely concur that the exhibition experience mirrors the motif of the exhibition: beauty, and what this meant to Mucha.

Alphonse Mucha was born in 1860 in Ivančicle. After being expelled from school due to poor academic performance, and subsequently having his application to enrol at Prague Academy of Fine Art declined, he went to Vienna to work as an apprentice scene painter in 1879. Eight years later, after progressing in his career as an artist Mucha moved to Paris to study at the Académie Julian and, a year later, the Académie Cola rossi. Over the next decade his life would drastically change. In 1894, he designed his first poster for the play Gismonda, featuring one of the most famous women in Paris at the time, actress Sarah Bernhardt. Paris fell in love with Mucha and his name became famous overnight.

Mucha’s style is known to most, even if they are unaware of his name. His form was very different to the contemporary designs that were seen around Paris at the time. Instead of bright and bold colours, which were very popular then, Mucha used pastels, and he used a graphic technique not really seen before.

The exhibition is split into three chapters: ‘Women – Icons & Muses’; Le Style Mucha – a Visual Language; and ‘Beauty – Power for Inspiration’.

I

WOMEN – ICONS AND MUSES

The mission of the artist is to encourage people to love beauty and harmony

– Alphonse Mucha

For Mucha, women were ‘creative forces to bring forth new beings’ (qtd. in Sato: 2015, 21); they are beautiful and wholesome, their eyes are serene and their expressions are comforting. Mucha believed that beauty symbolised ‘moral harmonies’ such as goodness and virtue (Sato: 2015, 8). Sarah Bernhardt was an icon, and certainly became a muse for Mucha. As noted above, they met in 1894 when he was commissioned to produce a poster for the play, Gismonda, a Greek melodrama in four acts by Victorien Sardou. In Quest of Beauty invites us to view several posters of Bernhardt, from La Dame aux Camélias (1896) and La Samaritaine (1897), to ‘La plume Art Edition’ poster. We are welcomed to perceive her beauty the same way that Mucha perceived it. He wanted to communicate with his viewers.

The success of Gismonda ignited a six-year work relationship between Bernhardt and Mucha. He continued to design the posters for her plays, but also her costumes, jewellery and stage sets. Concurrently, Mucha signed an exclusive contract with F. Champenois, a Parisian printer and publisher. It is his work with Champenois that established Mucha’s international fame. The style of the posters were referred to as ‘le style Mucha’, and later evolved into a new style which would become known as Art Nouveau.

His work with Champenois meant that Mucha could be found everywhere in Parisian advertising: on biscuit tins, cigarette promos, and advertisements for all kinds of alcoholic beverage…

What makes this exhibition special is that there was never an expectation that the images would survive, let alone in the wonderful condition that they are in. The study for the poster for Lance Parfum ‘Rodo’ (1896) is a prime example of this fortuitous preservation, and it is at this point that the familiarity of the art work and the influence Mucha had on other Modern artists becomes apparent.

Paul Greenhalgh and Claire Allerton argue that ‘the aesthetic ethos of Art Nouveau … is to do with the use of line’ (Greenhalgh, et al: 2015, 52). Although not used in every piece of Art Nouveau, the line becomes a signature element of the style, and Mucha uses it in such a way that it only ever enhances the image, becoming part of it rather than simply a frame. Alongside the incredible art works of Mucha, In Quest of Beauty is supported by artefacts from the Anderson Collection of Art Nouveau, with many pieces of jewellery and accessories, all portraying the infamous line and other motifs of Art Nouveau.

II

LE STYLE MUCHA – A VISUAL MESSAGE

During the birth of Art Nouveau, Modernism was bringing revolutionary changes, from Neo-Impressionism to Cubism. Mucha was one of the voices that spoke out against the assumptions that Modern art was going to be a passing phase. He believed that Art was eternal and that beautiful art helps to ‘elevate public morale and improve the quality of people’s lives, eventually creating a better society’ (qtd. in Sato: 2015, 79).

In 1896 Champenois devised the idea of decorative panels, which was the perfect marriage when combined with Mucha’s art. Mucha’s panels were printed on stronger paper stock to withstand the everyday use of the panels being utilised as screens. In Quest of Beauty teases us with the popular panel series ‘The Seasons’ (1896).

It is the detail and ornamental motifs which draw you in to each image. The wisps, the flowers, the geometric patterns and filigree tie the images together in a relationship with the woman at the centre of the image. There is much to see in just one poster. ‘Rêverie’ (1898) is an exceptional example of the fine work, and also one of the feature images of the exhibition. Mucha draws inspiration from multiple historical cultures such as Celtic, Gothic, Rococo and Greek, however, he leans very heavily on his Slavic roots, with many of his women wearing Slavic dresses.

Another group of works that magnify the talents of Mucha are his drawings. The level of detail in each piece, the pencil line work in some of his sketches are so fine and precise, they look as they could not possibly have been drawn by a human hand. The installation includes exquisitely detailed plates and cutlery, and sketches of the human form, such as ‘Figures Décoratives: Drawing for Plate 25’ (1904). Each line is perfect. The level of detail is incredible.

Whilst Mucha was drawing his way through Paris, he also obtained his first camera. He began to take photographs and collect them in a visual notebook to compliment his sketches. This chapter of the exhibition invites us to acknowledge his photographic studies of the female form, including a series referred to as ‘Dancing Nude’ (c. 1901), and is believed to have been an aid to his inspiration for his designs (Sato: 2015 104).

III

BEAUTY – POWER OF INSPIRATION

Mucha’s desire to work for his country’s political freedom through his art took him away from Paris, returning him to his homeland in 1910. From this The Slav Epic was born. For the next seventeen years, The Slav Epic became Mucha’s personal project, and he only otherwise took on commissions that were close to his heart.

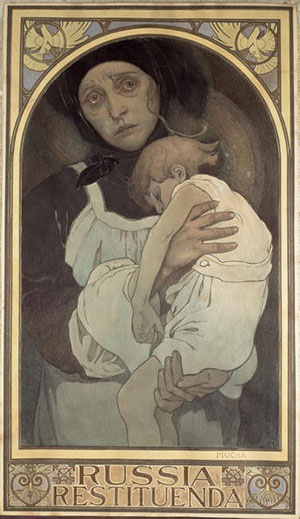

Women remained the centre of his work, now becoming a symbol of spirituality. It is the darker, almost Gothic, tones that seep through these pieces, and end the exhibition on a very different note to the one we started upon. ‘Russia Restituenda’ (1922) is the most haunted poster at the exhibition. It served as a ‘plea for help for starving children in the aftermath of the Russian Civil War (1917 – 1922), which paralyzed the country and killed millions through widespread disease and starvation’ (Sato: 2015, 136). The eyes full of kindness and purity were now filled with despair and anguish. The light pastel shades of purity are replaced with dark shadows and depths that go beyond his Paris period.

Ultimately, In Quest of Beauty is a journey from the birth of Art Nouveau, an education in beauty, a lesson in symbolism, and an insight into a political drive of a man who has captured beauty on many different planes, to many different depths, with an aesthetic importance than changed the world in the wake of Modernism. Although the installation at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art is a simple one, it’s an exhibition that leaves you in awe of the art that has been laid out before you, and is proof the Modernism wasn’t, and isn’t, a fleeting trend.

WORKS CITED

Greenhalgh, P. and Allerton, C. (2015) Verve and Logic: The Lineage of Art Nouveau. In: Sato, Tomoko. In Quest of Beauty. Czech Republic: Mucha Foundation Publishing, pp. 52-59.

Sato, Tomoko (2015) In Quest of Beauty. Czech Republic: Mucha Foundation Publishing.

FURTHER READING

Mucha, Sarah. ed., (2014) Alphonse Mucha. London: Malcolm Saunders Publishing.

Robinson, M. and Ormiston, R. (2009) Art Nouveau: Posters, Illustration & Fine Art from the Glamorous Fin de Siècle. London: Flame Tree Publishing.

Wolf, Norbert (2015) Art Nouveau. New York: Prestel.

Rate this post (NO WordPress account required)

[…] new art blog Vermillion Goldfish made a splash (sorry) this month with its first post, an in-depth look at In Quest of Beauty, the […]

LikeLike